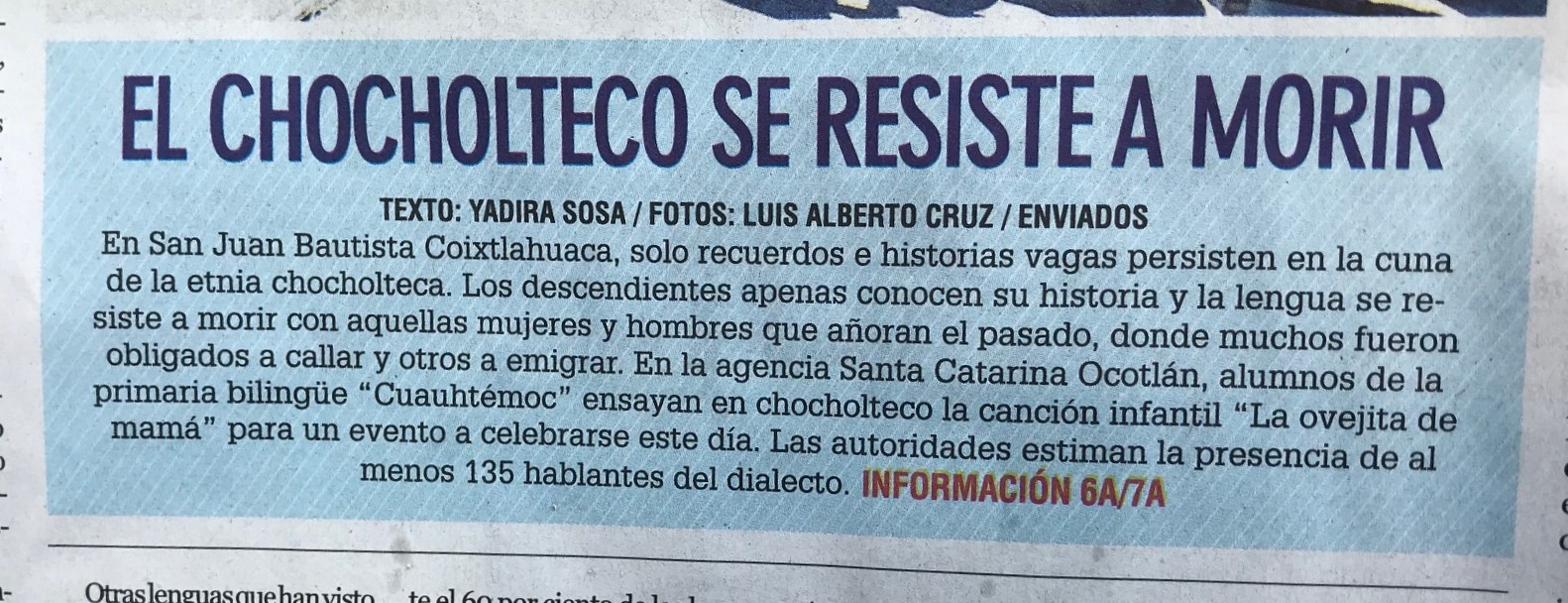

This winter, I tutored two oaxaquenosin English to help them gain a professional edge in digital communications and psychology. Now I have second thoughts about what I’ve done. The men’s parents are among the third of Oaxaca’s people who speak one of 16 languages used in that state. Zapotec, Mixtec, Mixe, Mazatec, Náhuatl and Chinantec are the largest groups. Smaller groups, like Chontal, are dwindling to a few elders. My students wished they spoke Zapotec but their parents didn’t teach them because of prejudice against indigenous speakers. Even without bias, Mexico’s 63 indigenous languages struggle to to exist against the barrage of Spanish published and electronic media.

Este invierno, enseñé inglés a dos oaxaqueños hombres para ayudarles ganan ventajas profesionales en las comunicaciones digitales y la sicología. Ahora, tengo segundo pensamientos sobre que hice. Los padres de los hombres son entre la tercera parte de oaxaqueños que hablan uno de las dieciséis lenguas usada en esto estado. Zapoteca, mixteca, mixe, mazateca, náhuatl y chinanteca son los grupos más grandes. Grupos más pequeños, como Chontal, están muriendo con las muertes de los ancianos. Mis estudiantes desearon aprender zapoteca pero sus padres los no enseñaron a causa hay prejuicio contra hablantes indígenas. Aún sin discriminación, las sesenta tres lenguas reconocidas por el gobierno deben de luchar para existir contra una riada de español en todas modas de comunicación.

Amigos de la Sierra norte de Puebla, una poeta y una maestra.

A friend in the Sierra Norte of Puebla is a radio announcer and a poet of Totonaco. His poems express with eloquence the values and spirit of his people. Radio and writing in his native tongue are his tools for making his native language the equal of Spanish in daily use. Another friend, formerly my Spanish coach, studies Náhuatl for her master’s degree. During my visit, we spent five hours in class. I came away understanding that indigenous languages offer many alternate insights into what it means to be human.

El gobierno mexicano soporta los canales de radios.

Un amigo en la Sierra norte de Puebla es un locutor de la radio y un poeta totonaca. Los valores y espíritu de su pueblo están expresados en sus poemas con elocuencia. Los poemas y la radio son sus instrumentos para poner la utilidad del lenguaje nativo en un base igual con español. Otra amiga, anterior mi instructora en español, estudia náhuatl por su maestría. Durante mi visita, pasamos juntos cinco horas en la clase de náhuatl. Salí entendiendo que las lenguas indígenas ofrecen perspectivas alternativas en siendo humano.

Until recently, the dominant political cultures in Mexico and the U.S. regarded the perpetuation of indigenous cultures as barriers to ‘civilizing’ the people (as whites or Europeans). Indigenous tongues that were suppressed before are largely ignored except as quaint artifacts for tourism. Now, the greatest threat to indigenous languages seems to be mass communications in Spanish (and English) and as the principle avenue for good jobs. Can an economy function with multiple languages? Europe does. Do indigenous languages have the capacity to express today’s technologies? I think so.

Las lecciones en nahuatl,

Hasta hace poco, las culturas políticas dominantes en México y lo EUA pensaban que la perpetuación de las culturas indígenas fue una barrera a civilizando la gente (como los blancos o europeos). Los lenguajes nativos que estuvieron suprimidos antes están ignorado principalmente ahora salvo como artefactos pintorescos para turismo. Ahora, se aparece que las amenazas más grandes a las lenguas nativas pueda ser las comunicaciones masivas en español (e inglés) y también como la vía principal para empleo bueno. ¿Podía una economía funcionar con lenguas múltiples? Europa hace. ¿Tienen los lenguajes nativos la capacidad suficiente para expresar las tecnologías de hoy? Creo que, sí.

Indigenous languages are as capable as English, Spanish or Mandarin for communicating modern technologies. One has only to study Mesoamerican ruins or the development of food crops to see their technology was often more advanced than that of Europe. The Mayas discovered and used the concept of zero centuries before Europeans. Like biological species, these languages and and cultures are distinct and integral parts of human ecology.

Las lenguas indígenas tienen tan muchos capaces como inglés, español o mandarino para comunicar las tecnologías modernas. Se tiene que solo estudiar las ruinas o el desarrollo de cosechas Mesoamericanas para ver que su tecnología era igual si no más avanzada a menudo de lo que en Europa. Las mayas descubrieron y usaron el concepto de cero siglos antes los europeos. Esas lenguas y culturas asociadas son partes distintas e integrales de la ecología humana así son las especies biológicas.

To lose a language is to lose its culture and its people. The extinction of an indigenous tongue subtracts from humanity’s larger fund of wisdom. Allowing indigenous tongues to atrophy and die is as barbaric as burning books. Spanish and English are the keys to powerful economic forces. There’s anything nefarious in learning English per se. But, the pressure and resources available to learn it for economic gain outweigh any countervailing efforts to cultivate indigenous languages. This troubles me. I can’t teach English without feeling like an agent of a globalism that may accelerate the suffocation of native tongues.

Para perder un lenguaje es para perder su cultura y gente. La extinción de una lengua resta del fundo grande de la sabiduría humana. Para permitir la atrofia y muerte de lenguas nativas es tan bárbaro como quemando los libros. Español e inglés están integrados como llaves a las fuerzas económicas poderosas. No hay nada nefaria en aprendiendo inglés por sí mismo. Pero, la presión económica y los recursos disponibles para aprenderlo son más grande que cualquier esfuerzas compensatorias para avanzar las lenguas indígenas. Esto me molesta porque me siento como un agente del globalismo podía acelerar la sofocación las lenguas nativas.